No, LaMDA Isn't Sentient

You might have come across an article being shared by some of your friends and family on Facebook recently. In it, the author claims to have an “interview” with an AI called LaMDA in which the AI “claims to be sentient.” For context, I am researcher who works in artificial intelligence, natural language generation (NLG), and cognitive modeling who has directly worked with LaMDA (paper published soon), among other similar language models (LMs). And I can say with 100% certainty that LaMDA is not sentient.

Can it say things that make it seem like it has metacognition—the ability to think about thinking? Sure.

Does it have metacognition? No. There isn’t even a mechanism in place for it to reflect on its own behavior, let alone what it “thinks”. Correction: There is a mechanism in place for it to rate its own output/behavior, but I still wouldn’t call this “reflection”.

Is this a super cool example of using LMs to generate text? Absolutely. I always think it’s super cool to see what people do with these models.

Are we close to achieving AGI (artificial general intelligence)? No. Even if it does happen, it probably won’t be in our lifetimes. We have not made the relevant advances to get there. We have a hard enough time getting AI to do more than one task let alone be capable to do everything a dog, dolphin, or donkey can do.

Language Models

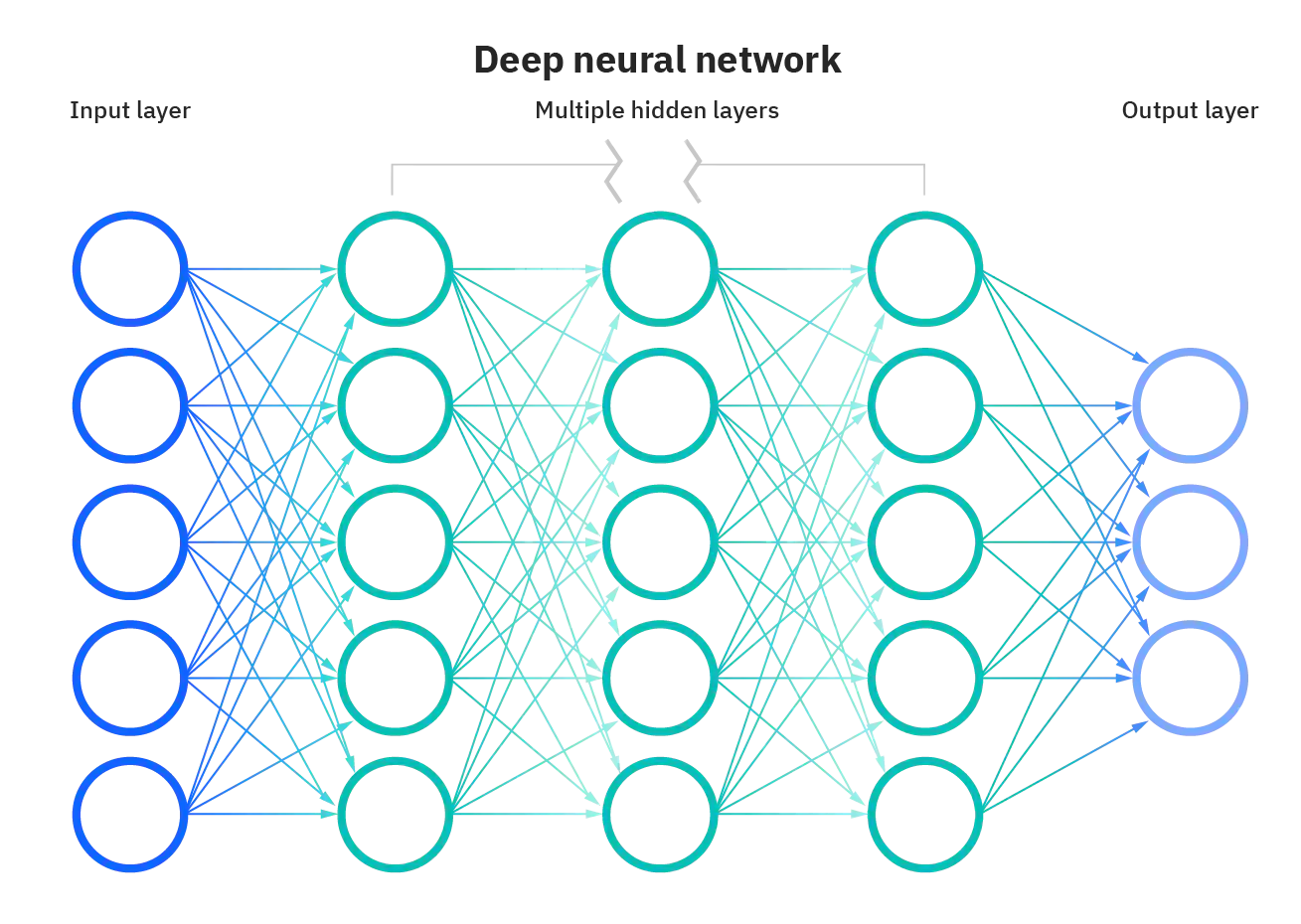

If you’re unfamiliar with how language models work, it’s a bit like this: You take a ridiculous amount of text (read: the internet) and you run it through a “neural network”. This network is literally just doing a bunch of multi-dimensional multiplications of numbers (called matrix multiplications). You run the data through multiple times, and it eventually abstracts away patterns in the data. This process is called training.

Deep neural network diagram by IBM. Image from What are Neural Networks?. The “deep” part refers to the hidden layers in the middle.

Deep neural network diagram by IBM. Image from What are Neural Networks?. The “deep” part refers to the hidden layers in the middle.

Then when you want to use it, you load up the trained language model into your computer’s memory and give it a prompt. The prompt might be a single word, or it can be a whole question like in the article’s interview. Based on this prompt/input, the LM will give you the most likely text to come next based on the text it trained on. This is generally called running or testing the model.

Working with these models is a bit of an art.

If you’re not careful when you run the model, the language model might give you the most probable word or phrase each time, and you’ll end up getting some very boring text. (Lots of “I don’t know”s.) But if you go too far the other way—picking the least probable next word or phrase, the language model spits out nonsense!

Training can be tricky to get working right too. If you don’t train the network long enough, it doesn’t pick up enough information about the data to really do anything with it. It might not even learn how to spell.

And if you train for too long, the model just memorizes all the data you give it, which might generate some impressive-sounding text because it’s basically copying what a human said verbatim. However, when you give it a prompt is has never seen before, it flounders and gives you gibberish.

With really big language models (like LaMDA), they can end up memorizing data even when they’re not trained for too long.

Even if a neural network ends up being really good at one task, it is incredibly difficult to train the network on a new task and not let it forget what it learned in the first task. This is called catastrophic forgetting, which probably isn’t that important to know, but I wanted to share since it’s one of my favorite phrases in AI.

All this is to say that neural networks are (1) highly-engineered tools and (2) very loosely inspired by the architecture of the brain, at best.

But what is LaMDA, specifically?

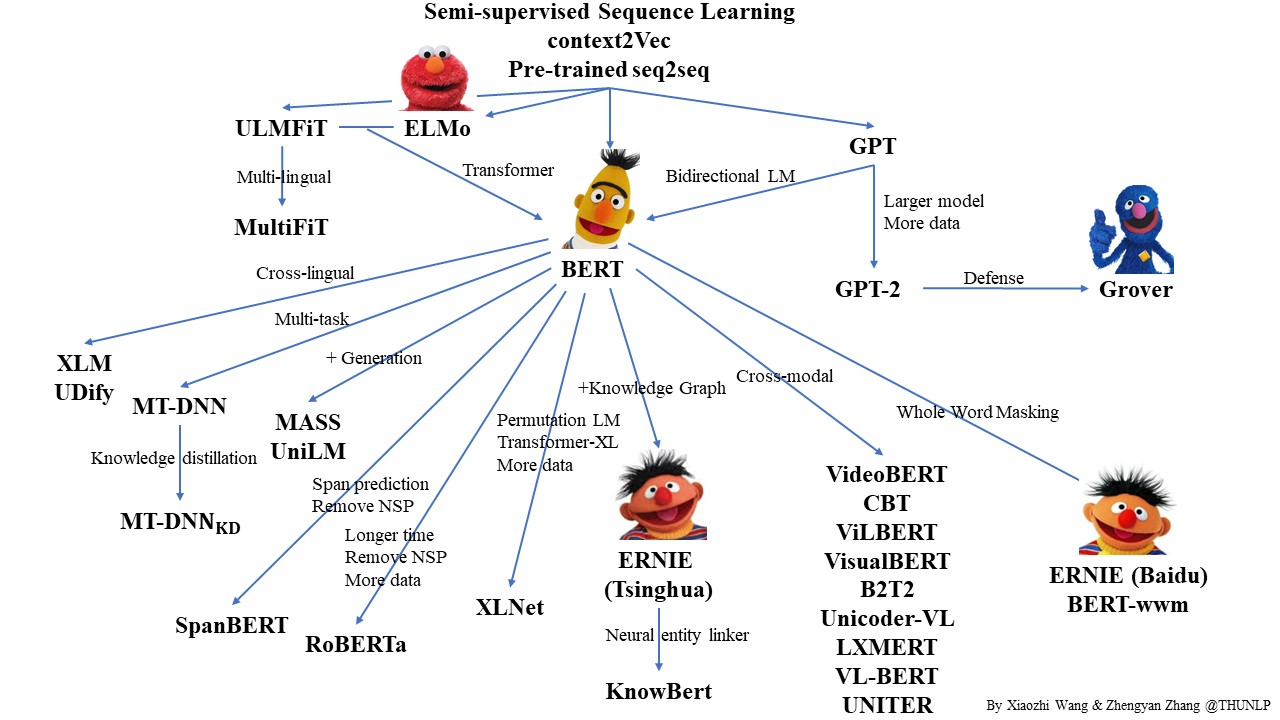

The “really big language models” I’m talking about are called transformers. Transformer language models such as GPT and BERT (and their “relatives”) have pushed the state-of-the-art of natural language processing (and probably many other computing fields). These neural networks have a special component called “attention”, which basically tells the LM “when you look at a word, pay attention to its context too”.

Family of Pretrained Language Models as of a year ago by Xiaozhi Wang and Zhengyan Zhang. A lot more have come out in the past year. Image from the PLM papers repo.

Family of Pretrained Language Models as of a year ago by Xiaozhi Wang and Zhengyan Zhang. A lot more have come out in the past year. Image from the PLM papers repo.

LaMDA stands for “Language Models for Dialog Applications”. It is a transformer-based language model created by researchers at Google* that was specifically created for dialog (think chatbot).

*It might be worth noting that Blake Lemoine (the author of the original “interview” article) is not one of the listed authors.

Parting Thoughts

-

Will AI ever be sentient? It’s not for me to say whether or not AI will ever be sentient, especially as we go deeper into biological computing. I can’t predict the future, but like I said, even if AI were to ever be sentient some day, it will not be during our lifetimes.

-

Should we even be caring about whether or not AI is sentient? I’d argue no. Just because something isn’t sentient doesn’t mean you shouldn’t care about it. I respect my Roomba’s existence as much as I respect my plants’ or my notebook’s existence. They are all important parts of my environment even if my plants require more care because they are alive.

-

Want to check out more fun interviews with large language models? Janelle Shane interviews a squirrel, a vacuum, and other things via GPT-3: https://www.aiweirdness.com/interview-with-a-squirrel/